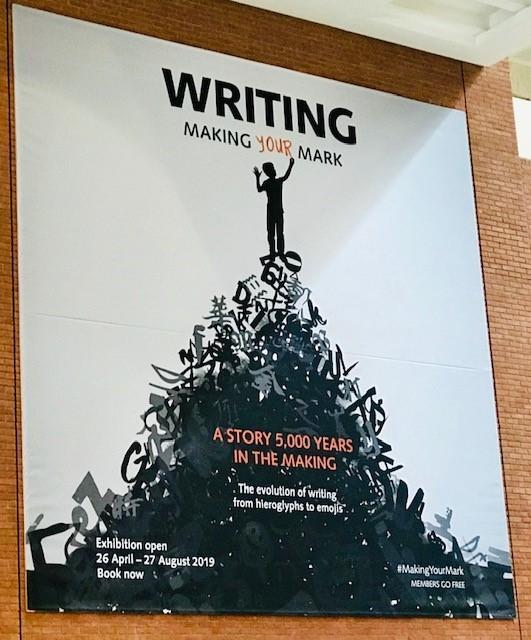

This British Library exhibition Writing – Making your Mark charts the development of the evolution of writing covering a 5,000 year span.

I enter the dim space and am led around the exhibits. The earliest scripts begin with the dawning of civilization, from Egyptian Hieroglyphics to Phoenician, Mesopotamian and Chinese scripts dating from around 3,800 years ago.

I learn that writing was first used by farmers and traders to name and number things, mark possessions and keep accounts using written systems and styles.

With this exhibition, the British Library has created a storyline and drawn on its own vast collection.

I begin my travels through time with wax and clay tablets used over 3,000 years ago. I stop to analyse a Mayan Limestone Stele dating from AD600 to AD800. Over 100 glyphs are marked, celebrating Mayan kings, their lineage and rise to power.

Another ancient tablet that catches my eye is Mesopotamian, dating from 2100 to 2000BC; its purpose was to preserve an account of wages paid to workers. Scribes would scratch, incise, carve and impress characters into moist clay using a stylus made from reed wood, bone or metal. I’m in awe of our human ingenuity.

I have fun with some interactive screens where I am presented with various obscure scripts from more than 40 different writing systems across the globe and am challenged to name them by answering multiple choice questions. I’m familiar with a lot of them but don’t know their names. Much to my amazement I recognize Coptic and Gujarati!

I stop and stare at a rare sample of calligraphy by Emperor Shomu and Empress Komyo dating from AD750 during the 5th Century, when writing came to Japan from China. I linger on the elegant brush strokes and feel their fluidity and grace. It is such a refined form of aesthetic writing and over time became one of the highest art forms in Japan.

I move onto the origin of our current alphabet, standardised by the Romans and strongly influenced by Etruscan inscriptions. In contrast, the Greek alphabet’s main influence was the Phoenician system.

By the 15th Century these Roman typeface and fonts used in Latin and Italian texts were wonderfully rounded, looped and joined. They have remained with us for centuries and still are the basis for most fonts used in word processing.

I love Niccolo Niccoli’s decorative letter work, a precursor to Aldous Manitius, the Venetian inventor of Italics. I pause to take in the way he combines Italic with Gothic dating from the early 1500s. It is so beautiful and I don’t think the art of calligraphy is in danger of ceasing anytime soon.

I move onto ‘Materials and Technology’ and learn a little bit about typesetting and printing with mechanical processes such as woodblock and hand presses; this eventually leads me onto typing and computing. I am challenged to write a phrase using small blocks of moveable letters, at first not realising that each line of text must be arranged in a mirror image. I manage to put a few words together with difficulty.

I turn around and discover that, now in the ‘printing’ section, I’m standing beside a huge 15th century wood and iron printing press. Its open drawers are packed with regimented metal letter blocks. I look up at this solid structure and take pleasure in its complexity. It towers over me. I notice the hinged frames and handles where the paper would be placed. I discover that it was used in 1477 to print Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the first major book printed in England by William Caxton. Around 600 copies were printed and fragments of 38 copies survive today. This copy in the British Library is one of the few that is still complete.

Beside this is the MacIntosh Apple II from 1977 with its eye catching rainbow apple logo. I wonder what something so innovative from the 20th century is doing beside something so antiquated; I then learn that this chunky offering from Jobs and Wozniak is the first machine to print and reproduce text using light. At the time it was ground breaking, simply unprecedented and state-of-the-art. I love it!

Continued next week

- Marisa Laycock moved from south west London to St Albans in 2000. She enjoys sharing her experiences of living in the city.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here